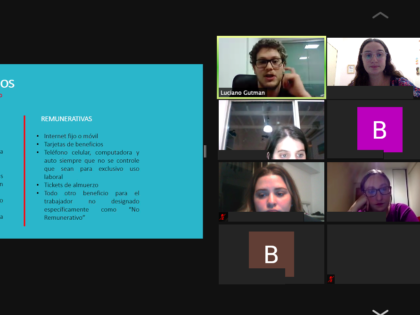

Gabriela Szlak y Lucia Suyai Mendiberri escriben acerca del proyecto de Ley de Protección de Datos Personales en One Trust – Data Guidance

Gabriela Szlak y Lucia Suyai Mendiberri escriben acerca del proyecto de Ley de Protección de Datos Personales presentado por el Senador Dalmacio Mera en One Trust – Data Guidance. El artículo resume los aspectos más relevantes del proyecto y su impacto en caso de que se apruebe. Además, se compara el proyecto con la Ley de Protección de Datos Personales vigente.

El artículo se encuentra disponible en el siguiente link https://www.dataguidance.com/opinion/argentina-evolution-data-protection-landscape y lo compartimos a continuación.

Argentina: Evolution of the data protection landscape

In 2018, the Argentine Executive Branch proposed a draft data privacy Bill (the “Bill”) which aimed to replace the current Argentine Data Privacy Act N° 25.326 (the “Data Privacy Act”). The Bill was a result of a multistakeholder process lead by the Access to Public Information Agency, the Argentine data privacy authority. The purpose of the Bill was to update the Data Privacy Act, which was enacted in 2000, in line with the latest international standards. The Bill was also considered as an important tool for the country to maintain its adequacy standard based on article 45 of Regulation (EU) 2016/679[1] (“Argentina Adequacy Decision”).

In 2020, the Bill lost its parliamentary status, and therefore, the Congress cannot discuss it. Despite this, the Argentine Data Privacy Authority has been updating the practical application and interpretation of the Argentine Data Privacy Act through several dispositions and resolutions. This practice has been successful so far in filling the gaps of the current Data Privacy Act. Still, the shared view of local experts is that new, freshly updated Data Privacy Law is preferable to improve the current situation. In said context, the Draft Law S-2986/2020 presented by the Congressmen Dalmacio E. Mera (the “Draft Law”)[2] has incorporated most of the text of the Bill and the latest regulation issued by the Argentine Data Privacy Authority, as well as the international standards on data privacy law. The purpose of the Draft Law is, on the one hand, to ensure data subjects’ rights under the light of the technology evolution and the challenges that emerged over the past 21 years and, on the other hand, to maintain the Argentina Adequacy Decision[3] after the adoption of the European General Data Protection Regulation (the “GDPR”).

Argentine Data Privacy Law Jurisdiction

The Data Privacy Act’s scope of application has been subject of extensive scholar and jurisprudence discussions, given the Act does not resolve it directly.[4] With this respect, in 2009 the Argentine Data Privacy Authority provided that the Act was applicable to all private databases that were not intended to be for private use.[5] The Draft Law embraces this understanding and closed any possible debate by providing under section 3rd the private use exception to the Act’s application[6] and regulating under Section 4th the scope of its application.

The Draft Law adopts the extra-territorial jurisdiction principle, providing its application in the following cases: (i) the data controller is established in the Argentine territory, even if the personal data processing is performed outside this territory; (ii) the data controller is not established in a territory where the Argentine Law does not apply by virtue of the international law; and (iii) the data subject is an Argentine resident, regardless of the location of the Data Controller, except when the Law where the Data Controller is based, results more favorable for the protection of the data subject’s personal data, at the choice of the data subject.

Principles applicable to the data processing

As the Data Privacy Act, the Draft Law sets forth several principles that should govern the processing of personal data. It could be noticed that the “Loyalty and Transparency”, “Purpose”, “Minimization” and “Accuracy” principles are already provided under the principle of “Data Quality” of the current Data Privacy Act.

The principle of “Loyalty and Transparency” states that personal data processing should not be conducted by fraudulent or misleading means, which is similar to the principle of “Data Quality” which provides that the personal data should not be collected by disloyal, fraudulent or by any means contrary to the Data Privacy Act provisions. However, the principle of Loyalty and Transparency incorporates the “transparency” approach to be considered within the personal data processing and is related to the duty to provide clear and accessible information to the data subject.

The principle of “Purpose” states that “Personal data must be collected for specified, legitimate and explicit purposes, and must be processed in an appropriate and targeted manner.” (Draft Law, Section 6th), and the principle of “Minimization” states that “Personal data must be processed in a way that is adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which it was collected.” (Draft Law, Section 7th). Both wordings are similar to the principle of Data Quality, provided under the Data Privacy Act, Section 4th[7]. The same consideration is applicable to the principle of “Accuracy”: its language is analogous to Section 4.4 of the Data Privacy Act which provides that “personal data shall be exact and updated as applicable”, as well as Section 4.5, which sets forth that inaccurate or incomplete personal data should be cancelled, substituted, or completed.

The Draft Law sets forth a principle related to “Data Retention”, comparable once again to the existing principle of “Data Quality”, which provides that personal data should not be retained and shall be destroyed when it is not further necessary or relevant to the purpose for which it has been collected. However, Section 9th of the Draft Law, as a novelty, enables to retain personal data even for longer periods of time, as long as this retention is due to archive purposes related to the public interest, scientific or historical research, or statistics.

Accountability

One of the highlights of the Draft Law is the “Accountability” Principle provided under Sections 10 and 37. In accordance with this principle, Data Controllers and Data Processors shall undertake organizational and technical measures to grant an adequate, lawful and safe personal data processing, and these measures must allow evidence of its effective implementation before the Argentine Data Privacy Authority.

Section 37 of the Draft Law provides guidelines for the principle of “Accountability”, foreseeing that measures should be appropriate to the methods and purposes of the personal data processing, its context, the categories of personal data processed, and the risk to the data subjects’ rights inherent to the personal data processing.[8]

Consent and other legal basis for personal data processing

While the Data Privacy Act foresees data subject’s consent as the ground for lawful personal data processing (admitting restrictive exceptions), the Draft Law extends the basis for legal data processing by including the following cases: (i) the data processing derives from a legal relationship between the data subject and the Data Controller, and it is necessary to its development or fulfillment; (ii) the data processing is necessary to safeguard the vital interest of the data subject; (iii) the processing of the data is necessary to comply with a legal obligation of the Data Controller (i.e. Data Controller compliance with legal duties such as the ones provided under Labor Law); (v) data processing is carried out in the exercise of the Government functions; among others.

Another novel aspect of the Draft Law is that it foresees not only to the express consent but also the tacit consent, which can be used as a viable consent. This tacit consent will be evaluated according to the circumstances, and according to the data categories at stake and the data subject’s reasonable expectations. It should be noted though, that an express consent must still be required with respect to special categories of data such as health-related data or sensitive data.

Lastly, the Draft Law specifically foresees the data subjects’ right to withdraw their consent. In this regard, it shall be noticed that, although it is not expressly provided for under the Data Privacy Act, following the principles of the Argentine Civil Law, data subjects were always entitled to revoke their given consent.

Minors’ Consent

While the Data Privacy Act does not foresee cases of minors or adolescents,[9] Section 18th of the Draft Law does, by providing that the consent given by 16-year-old individuals shall be considered valid within services designed or adequate for them. In the case of children under 16, their personal data processing should be consented by, if the consent is granted by their tutors or parents. data controllers shall undertake reasonable measures to verify the tutors’ or parents’ consent for the processing of children personal data under 16.

Security Breach Reports

The Data Privacy Act does not provide an explicit obligation for notifying security breaches. However, the Argentine Data Privacy Authority has included this report as part of the guidelines applicable to comply with the security measures required by said Law.[10] The Draft Law closes any possible debate in connection with the report obligation by expressly providing that security incidents compromising personal data shall be notified to the Authority and to the Data Subjects within 72 hours of its discovery.

Data Subjects right not to be Subject to Automatized Decisions

The Data Privacy Act only foresees the right not to be subject to automatized decisions in connection with judicial or administrative decisions, while Section 32 of the Draft Law, in accordance with international current trends, extends this right to any decisions.[11]. Notwithstanding, the Draft Law admits certain exceptions to the exercise of this right, as it is the case of the consented data processing, or when the automatic processing is authorized by Law or when it is necessary for the fulfilment of the Data Controller’s obligations pursuant to a contract with the Data Subject.

Right to Data Portability

Although there are admitted exceptions, the Draft Law entitles Data Subjects to request its personal data to the Data Controller, in a structured, commonly used, and machine-readable format, as well as to request its personal data to be transferred to another Data Controller.

Other Best Practices which the Draft Law Enforces

Among others, the Draft Law incorporates, as binding principles, the principles of privacy by design and privacy by default,[12] which are currently provided under some dispositions, as recommendation or best practices. Following this principle, the Draft Law includes the obligation to conduct data privacy impact assessments, prescribing the issues to be addressed,[13] and the appointment of the Data Privacy Officer for specific cases.[14]

Sanctions

If the Draft Law is passed, sanctions will be increased: the fines are established at 550 minimum wages.[15]. Also, the Draft Law foresees suspensions and closures of the respective establishments. It is expected by most privacy law practitioners in the country that the reasonable increase and effective application of the fines, which are currently regarded as low, will improve compliance with the law in the benefit of data subjects.

Conclusion

The Draft Law would enter into force two years after it is approved. During said period, entities are expected adequate their practices to the new standards and principles regarding the processing of personal data if they are not yet in compliance with them.

Moreover, despite the Draft Law enactment, it is highly advisable for companies processing personal data to check their compliance with the data privacy law but also with international standards of compliance and best practices. These standards are crucial, the Argentine Data Privacy Authority will most likely continue issuing regulations to update the Law to international standards and best practices, even if this Draft Law is never passed. It is expected that some of the issues introduced by the Draft Law will be, nonetheless, binding in light of new Agency dispositions.

This article has addressed some of the highlights of the Draft Law but is not intended to be an exhaustive analysis. Moreover, the Draft Law could be modified within the congress discussions, and thus some of the aspects addressed herein would need to be subject of further consideration.

Lucia Suyai Mendiberri

Gabriela Szlak

[1]2003/490/EC: Commission Decision of 30 June 2003 pursuant to Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the adequate protection of personal data in Argentina. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32003D0490

[2] Draft Law is available at: https://www.senado.gob.ar/parlamentario/comisiones/verExp/2986.20/S/PL

[3] The fundamentals of the Draft Law indeed state that it has been based on the Bill passed by the Executive

Branch in 2018 and has incorporated changes and additions to ensure a proper data protection. Also, it is recognized that the Draft Law has been inspired in several international sources such as the General Data Protection Regulation (2016/679), the personal data protection standards for Ibero-American States dated June 20, 2017, and the Organic Law on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights of the Spain 3/2018. Lastly, is also declared that the initiative aims to maintain the adequacy decision of the European Commission. the Draft Law is available at: https://www.senado.gob.ar/parlamentario/comisiones/verExp/2986.20/S/PL

[4] It was argued that the Data Privacy Act was only applicable to the databases aimed to provide reports – as it is stated under section 1st-.

[5] Furthermore, the Authority set the standard that a database is not considered “of private use” when its data is used to conduct evaluations that affect or impact data subjects’ rights. Dirección de Protección de Datos Personales Nota DNPDP Nº 816/2009-3471.

[6] In principle the Draft Law would be applicable to any data processing other the one deemed “private”. The private use of data that should not be subjected to the Draft Law is the one conducted by a human person for its or its family’s private use.

[7] Data Privacy Act, Section 4.1 related to Data Quality Principle states: “The personal data collected for the purpose of processing must be true, adequate, relevant and not excessive in relation to the scope and purpose for which they were obtained”; and Section 4.4 states “The data being processed shall not be used for purposes other than or incompatible with those for which they were obtained.”.

[8] Also, Draft Law Section 37th sets forth the minimum aspects that should be addressed: (i) internal procedures to adopt the measures; (ii) procedures implementation of attending the data subjects’ requests in connection with their rights; and (iii) it shall be foreseen internal and external audits to supervise the compliance with the measures undertaken. Moreover, it is specially provided that the referred measures should be adopted in a manner to evidence its compliance before the Argentine Data Privacy Authority and that privacy policies or autoregulating systems shall be adopted as they will be considered by the Authority to corroborate the compliance by the Data Controller.

[9] The Argentine Data Privacy Authority issued Disposition AAIP 4/2019 setting forth guidelines and best practices indicators for the Data Privacy Act application addressing the minors and adolescents’ cases. Guideline Nº5 of this document states that minors and adolescents’ consent shall be considered by applying the progressive autonomy principle. If the person is deemed uncapable of given its consent, parents or tutors should give their consent for their personal data processing.

[10] Disposition AAIP 47/2019.

[11] Data Privacy Act, Section 20 states: “Judicial decisions or administrative acts involving the assessment or evaluation of human conduct may not be based solely on the result of the automated processing of personal data that provides a definition of the profile or personality of the data subject”.

[12] Draft Law, Section 38.

[13] Draft Law, Section 40, 41 and 42.

[14] Draft Law, Section 43 and 44.

[15] In January 2021, this amount is approximately 4.5 million pesos.